Yesterday, Dean Baker of the Center for Economic Policy and Research posted an article that references an interesting policy brief put out by the Boston Fed on the relationship between unemployment and job vacancies. [1] Both Baker’s article and the brief are more than a little bit wonky, but worth reading, especially if you are confused—as I often am—about whether the oft-cited “skills mismatch” argument helps or hurts our case for greater public investments in job training and adult education.

Also known as structural unemployment, the skills mismatch argument, in a nutshell, attributes our current high unemployment numbers to workers not having the skills that employers need. Baker and others think this explanation for our current unemployment problem is way off base, and he kvetches about this on a regular basis on the CEPR Blog and his own blog, Beat the Press. As he and fellow critics argue, if we were truly suffering from structural unemployment, you’d expect to see big wage increases for those who do have the skills employers need—but that hasn’t happened. Moreover, the increase in unemployment during the recession has been pretty uniform across most occupations and industries, and on workers at all education and skill levels. (In the world that I work in, people often cite the lower unemployment rate for highly educated workers over less educated workers as further evidence of the skills mismatch, but this is actually always the case, and thus tells us nothing about whether or not the economy has a structural unemployment problem.)

Critics of the skills mismatch theory argue that the rise in unemployment is actually due to an aggregate drop in demand across the economy. (Best example of this is the collapse of the housing bubble, which depressed demand for new housing, plus had ripple effects across the economy, as people who lost value in their homes reduced their spending, which leads to businesses contracting and laying off workers.) Their argument is pretty convincing, at least when looking at the economy as a whole.

Getting back to Baker’s post yesterday, apparently Team Structural Unemployment has recently been highlighting an outward shift in something called the Beveridge Curve as a point in their favor. Baker’s post and the Boston Fed brief do a good job shooting down this argument, which I won’t go into here since you can read what they have to say for yourself.

The point is, every time I read an argument claiming a major structural unemployment problem—at least at the macro level—it seems to be pretty deftly shot down by critics.

Nonetheless, I don’t see why the lack of evidence for structural unemployment should diminish the case for job training and adult education as an investment. I suppose that there is a danger that overzealous arguments dismissing the skills gap might suggest to some that there is no point in providing job training or adult education at all, but I don’t think that’s a significant worry. At a city or regional level, I don’t know why some unemployment couldn’t still be the result of a structural change even if that’s not the case for the country overall. For example, I know when manufacturing abandoned northern New England in the 1990s, new higher-skilled jobs did appear—even if not enough to replace all the lost manufacturing jobs—and these jobs required higher reading and writing skills. And in the comments section to Baker’s post, Bob Spencer argues that while it does appear that the economy is not generating enough jobs (especially good jobs), we do have a “structural” problem that existed pre-recession, noting low graduation rates in Virginia, where he lives. He suggests that there is a shortage of both jobs and a “quality” workforce.

I think that’s about right. On a macro level the numbers aren’t there to support the argument that there is a large-scale structural unemployment problem—at least no more than was the case pre-recession. There was—and is—a lack of economic opportunity for low-skilled workers—one that can be addressed in part by investing in adult education and training. But if the jobs aren’t there, no amount of training will fix that, which suggests that, at best, there are limits to “educating our way” to prosperity, as the Secretary of Education likes to say.

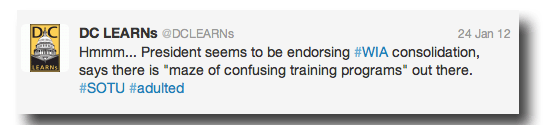

Which is why I wouldn’t mind pivoting away from the skills mismatch argument as a key message in our advocacy. Not because it’s wrong—as I explain above, I don’t see why skill deficits couldn’t still be a factor in certain parts of the country in some situations—but because it’s troubling to me that this argument may play into the hands of those who stand in the way of policies that would benefit low-skilled, low-income adults every bit as much as education and training do, and shift too much of the burden of solving our unemployment problem on the unemployed themselves. As Jared Bernstein, another structural unemployment critic, writes here: “a failure to discern structural impacts from cyclical ones…. allows policy makers to nudge aside weak demand as a key diagnosis and instead blame the unemployed for not having the skills employers need.”

The problem I have with the skills gap argument is twofold: First, claiming—incorrectly—that our unemployment is structural works against the notion of using government spending to generate more demand in the economy. After all, if unemployment is largely due to a skills deficit, and not demand, than increasing demand through government spending won’t do much good. But flat or reduced government spending not only limits potential job growth in the economy, it limits federal spending available for things like… more job training and adult education. In other words, a widespread belief in structural unemployment contributes to the lack of support for increasing government spending, and increasing spending on federal job training and adult education programs is what we are advocating for in the first place.

Secondly, the widespread belief in the skills gap is a distraction from other policies that would make more of the jobs that are available now into good jobs (those that pay a living wage, provide health benefits, etc.). (I would argue, in fact, that a low-skilled worker without a high-school diploma, making minimum wage and receiving no health benefits, might be way better off in the short-term with an immediate wage boost and health insurance than with enrollment in a GED class, even if improving their skills/credentials is likely to increase their long-term economic prospects. More importantly—the economic stability that would likely result from that wage/benefit increase would likely put that person in a better position in the long-term to take advantage of and succeed in additional education/training.)

There is no doubt that there are large numbers of people who would benefit from adult education and occupational skills training, but that was true before the recession caused the drop in demand that is largely responsible for the high levels of unemployment we have today. In other words, the recession doesn’t seem to have exacerbated the structural employment issues that existed pre-recession.

We also know that there is actually a larger set of interconnected povery-reducing policies beyond education and training that impact the lives of low-income, low-skilled adults—and that support overall economic growth as well. Putting aside the skills gap argument, and talking about the need for job training and adult education in terms of increasing economic opportunity and improving the quality of our workforce might be a better way capture all of these interconnecting issues while still being responsive to employer needs.

POSTSCRIPT:

A few months ago, Bernstein suggested a possible way to make the case for skills that doesn’t rely on the notion of a skills deficit:

I still think we’d have a better economy/society with higher levels of educational attainment…I’m quite certain, in fact. It’s wrong to think that the jobs of the future all will demand wicked high skill sets—we’re going to need lots of home health aides, cashiers, security guards, equipment technicians, child care workers, along with high-end engineers. But to have smarter, better educated people in all of those jobs makes all the sense in the world. We want our child care workers and home health aides to be highly trained—not as Ph.Ds in robotics, but in their fields.

In other words, it doesn’t necessarily require a skills mismatch economy to make the case for higher skills.

[1] “What Can We Learn by Disaggregating the Unemployment-Vacancy Relationship?” by Rand Ghayad and William Dickens. While issued by the Boston Fed, it’s worth noting that this paper does “not necessarily reflect the official position of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System.”